Where’s all the long carbon?

If the Bigger Short implies that everyone has a short position in carbon emissions, where are we going to find the “long carbon” to cover that position?

There’s not enough long carbon to cover your short position. Or anyone’s really. Not now, nor in the near term. It’s just math, a little bit of mass balance equations, and a little economics.

A few weeks back, I wrote about the Bigger Short of carbon emissions. Put briefly, the idea is that nearly every company is merrily emitting carbon dioxide and assuming that it’s price tomorrow will be exactly what it is today - zero. But governments will get serious about reducing emissions, that is to say, making them scarce, or else we will make much of the earth uninhabitable1. And as they do, companies will either (1) reduce their emissions, (2) reduce their earnings, or (3) find “long carbon” with which they can cover their short position.

Companies generally do not like to be in the business of commodities trading unless that is their core business. Right now they are all holding uncovered carbon futures like there’s no tomorrow2. Today I’ll argue that there’s not very much long carbon to go around to match that short position, because we’re not doing the math correctly, and so some companies that think they’ve “covered their short” may not have. Many if not most imagine that these counterfactual credits will take care of the problem, but they will not - they don’t actually reduce emissions, so they don’t constitute “long carbon” you can use to net against your short position. This is related to but different than the chasm3 between net zero and carbon neutral

To put a fine point on it, if your company is planning to reduce its footprint to zero by purchasing a bunch of credits from people who say “we would have cut this forest down, but we didn’t”, then you do not have a plan for a world in which we actually reduce emissions. Those counterfactual credits won’t have value in a world where emissions are priced/scarce - instead you’ll actually need to pay someone who is growing a new forest (and hence pulling CO2 out of the atmosphere) or running a machine that does the same thing - and you’ll need to pay them more than the prevailing price of carbon, otherwise they’ll just sell on the open market. But why would you pay them more than you can get on the open market? If these questions don’t make it clear, I think there’s a commodity market at work here - it’s just currently non-functional because the price is stuck at effectively zero4. Every company needs a plan that recognizes this5.

There are a lot of clever ways to reduce emissions, and I’ll call them all “avoidance”6 - if you purchase energy produced from fossil fuels, you can instead purchase renewables. If your delivery trucks make wasteful extra trips you can cut them out (in fact, if you’re a CFO or COO you’ve already done this kind of waste reduction many times, it’s just that the cost of waste is about to go up). If you purchase new raw materials, perhaps you can purchase more recycled. If you have a fleet of big cars, you could over time switch to smaller and more efficient cars. There are a lot of ways to use less fossil fuels and emit less, but if you add all of the ways that are available that are not being used, my intuition is that avoidance can only account for a small portion of what we emit.

Reducing earnings by just paying the cost of emissions and continuing as normal is straightforward, but not generally a great idea for anyone who works in a competitive economy. So let’s set that aside for the moment, I’ll come back to it.

As far as “long carbon” goes, the natural temptation has already been to “buy our way out” by purchasing offsets to carbon emissions. These are kind of like the greenhouse gas version of medieval indulgences (“you sin, you pay a fee, presto change-o, no sin!”). Currently, as Ed Smith pointed out last week, many offsets are based on counterfactuals (“if you hadn’t paid me $500, I would have emitted 100 tons of CO2, but now that you have paid me $500 I will not emit any of those tons, so you have paid $5/ton and you can emit 100 tons and the world will be no worse off!”). As I laid out a few weeks ago, Big Tech is making enormous use of these counterfactual credits to make claims that they are already carbon neutral7.

But all of these counterfactual credits become effectively worthless in a world where there is actual pricing or true enforced scarcity. Let that sink in for a second, because that’s a big deal. Here’s an example - let’s say that there’s a price of $100/ton of CO2 out there8. If you could have emitted 100 tons you would have paid $10,000 (=$100/ton * 100 tons) in carbon fees. If you choose not to, you pay $10,000 less in carbon fees. Why would you accept less than $100/ton from me to choose not to emit those 100 tons when you could just not emit them and not pay the taxes? Why would I pay more than $100/ton when I could just pay my taxes? All those “if you pay me, I’ll do X instead of paying my taxes” credits will just evaporate - EXCEPT for those which actually involve sequestration, or pulling carbon out of the atmosphere9.

BIG IMPORTANT FORMULA ABOUT PROFITS: If you can pull carbon out of the atmosphere for a cost of less than the prevailing price, you will make profits equal to [price of a ton of carbon emissions - your cost of pulling a ton of carbon out of the atmosphere] * [# of tons you can pull out of the atmosphere] * [some discount factor in case your tons aren’t permanently out of the atmosphere, or result in another ton of emissions somewhere else etc].

We’ll come back to that discount factor again and again, because fundamentally this is a risk management problem linked to a scale problem. But the important part for now is that counterfactual credits will not have any value in a world of priced carbon emissions (because they do not change the amount of carbon in the atmosphere, and changes in that amount of atmospheric carbon in the form of emissions & removals is what is actually being priced, not hypothetical or foregone emissions); only truly proven sequestration credits have value in a world of priced carbon emissions.

There are all sorts of corollaries and complexities about property rights and liability here - because importantly all emissions will need to be priced. If you own a million acres of loggable but unlogged forest land, today you might be using that acreage to generate credits by not logging it. After a price is in effect, no one will pay you for not logging it - your land will just either emit CO2 or sequester it and you’ll have to pay if you log it10. Theoretically you’ll earn credits as it grows and sequesters carbon too. On average, if it’s a mature forest that’s not changing very much, let’s assume that in an average year its CO2 is constant so you won’t earn much if it’s just sitting there in status quo. But what happens if there’s a forest fire and your forest burns down, emitting millions of tons of CO2? Are you liable? Well, it’s probably true that if you had a million acres of bare crop land and you chose to grow forests on it, you’d get paid for sequestering all that CO2 in the trunks, leaves and roots. So why wouldn’t you be liable for the emissions if your forest burned down? Will we see insurance products for all the carbon sinks in the world that could potentially be released? It would certainly align incentives. Governments aren’t always great at this, but again I’d be surprised if we don’t eventually see a holistic system that recognizes that “a ton is a ton is a ton no matter where or how it is emitted, no matter why or by who”.

But let’s get back to the core points that (a) none of these counterfactual credits have value in a world of priced emissions, and (b) that paying someone else for avoidance will likely go away as an option because they’ll get the same economics for avoiding those emissions themselves. So that means that the only long carbon available to cover companies’ short positions (ie, their emissions) will be avoidance or sequestration. Sequestration is in remarkably early stages - direct air capture has promise, but is expensive and energy intensive, and if energy costs increase due to carbon pricing it will become more expensive. CCS (carbon capture and storage, or basically injecting liquid carbon dioxide underground) is widely used by oil companies already under a tax program called 45T, but has its skeptics. And nature-based solutions like kelp farms, mangrove farms, or regenerative farming have tremendous potential for scale, but are in the early days of proving that they can be managed at significant scale in a way that truly demonstrates that CO2 has been taken out of the atmosphere and stays out. If the near ideal form of a carbon credit is direct air capture or DAC (you run a machine, and make mineralized CO2 that I can weigh, measure, and store so I can tell where it is and point to it, and I know with dead certainty that it isn’t going anywhere, or even if it does I can measure how much is left), then the rest of these methods have a lot to demonstrate - which means that that “discount factor” I referenced up above is going to be fairly low for DAC, and substantially higher for all these other forms of sequestration credits.

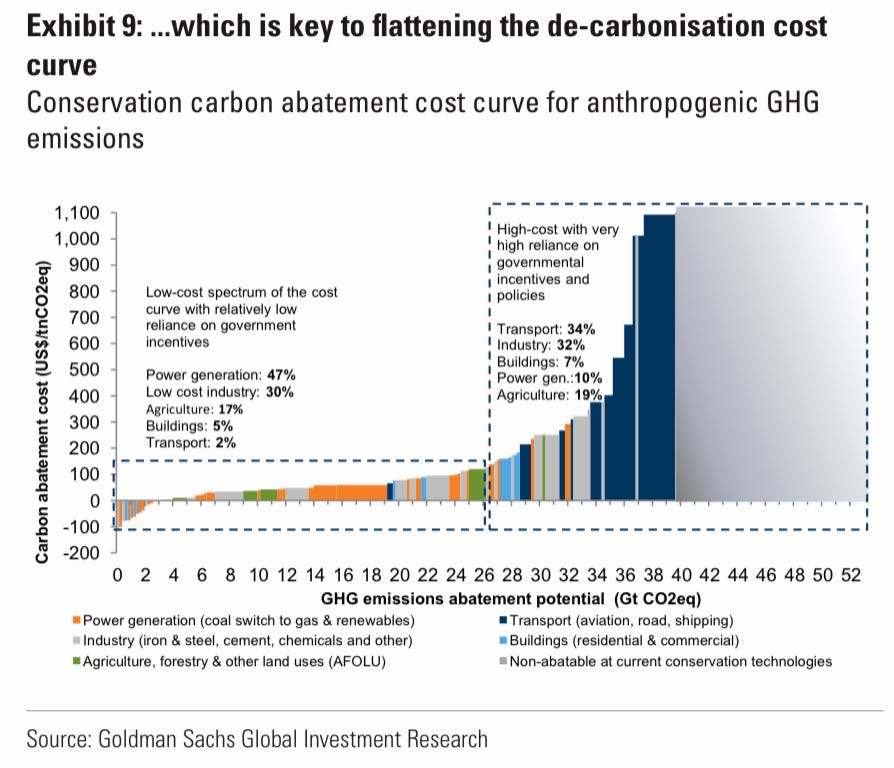

Look at the Y axis in the graph below from Goldman Sachs’ excellent Carbonomics report. We emit about 52 Gt of CO2 per year globally today. That’s the width of the graph on the X axis. The set of decarbonization stuff11 we can do that is below $100/ton (a price that’s within view in Europe’s oil & steel sectors but very few other places and certainly not in the US) is only about half of that, and if we’re going to get to a true Net Zero (meaning only sequestration counts against emissions), we need to get to a bunch of the projects way out on the right that cost… $500-$1000 per ton or way beyond into the unknown?!?! Maybe there’s room for optimistic thinking that agriculture or other nature-based solutions could be vastly underestimated12 in potential here, and it is certainly early days, but based on this analysis alone it’s not looking particularly good.

What we really will need, and will certainly have when pricing becomes widespread, is a means for financializing all the risks in these credits. Insurers will likely provide “carbon credit insurance” to make up the difference between any individual credit and an idealized one such as a DAC credit. This is exactly what mortgage insurance does today - if you default on your mortgage, your mortgage insurer makes up the difference to your creditor. Similarly, if a set of sequestration credits “go bad” by being impermanent, insurers should “pay for equivalent credits at the market rate”. Securitization will also be important - though it got a bad rap in the financial crisis because we were issuing mortgages to anyone who could breathe, securitizing these crappy subprime loans and claiming they were nearly risk-free, it’s one of the major financial innovations of the 20th century. Securitization will certainly have its place in a world of uncertainty about individual carbon credit risk, but the ability to diversify across carbon credit risk pools. And we’ll have a forward carbon curve, the same way we have an interest rate curve - we’ll be able to see what the market thinks the cost of a ton of carbon will be in 2 years or 5 years or 20 years and buy contracts to hedge risk. Hint to entrepreneurs: all of these things are desperately needed now, and whoever has a lead when pricing occurs will be in a position to create a tidy profit.

But none of those tools of finance (insurance, securitization, forward price visibility) can make up for the fact that there isn’t very much long carbon available, and the sources which can make it available won’t turn on a dime - they will need multiple years to make these large sources available. Viewed from a policy perspective, we should get going now (we should have gotten going on this in the 1980’s and almost did, but that is water under the bridge - handwringing is not very useful). Viewed from the perspective of company management, this is an opportunity to get ahead of a vast “mega trend” that will drive winners and losers in every sector. Viewed from an investor’s standpoint, this could be the mother of all asset price dislocations as markets realize just how much this embedded short will drive asset prices.

If anyone has been paying attention to US markets (or Twitter, or really any media) in the past few months, they’ll remember GameStop and the concept of a short squeeze. That’s when there’s not enough “long” of an asset available to cover a bad short position. Now, before everyone starts squawking that if we have regulation and pricing, the price isn’t going to skyrocket above the imposed price, I agree. If government says that the price is $50/ton, and there isn’t enough long carbon around to cover your position, and the projects you have to do to cut emissions will cost you more than $50/ton, then you just pay the tax - it’s the cheapest thing to do. But the issue is that this is a game of public finance with a couple of known end-states; a much less inhabitable world or Net Zero. If we are going to get to Net Zero (true Net Zero, meaning only sequestration credits count), then governments will push prices on carbon up and up and up until we get there. They may well decide we need to get to Net Negative (meaning we are pulling CO2 out of the atmosphere to get it back down to closer to our pre-industrial revolution levels). That will likely require very high prices, which is effectively a government created short squeeze. Anyone who’s not ready for that mother of all asset price dislocations should be getting ready.

When disclosure requirements come (and they are rapidly approaching, at least for public companies, even if some are readying to put up a fight), it will be like Warren Buffet’s famous tide - “it’s only when the tide goes out that you discover who’s been swimming naked”. There’s a lot of naked short position on carbon emissions out there, and not very much long to go around if you do the math right.

And many other horrifying consequences too. I’m not trying to be glib, I just believe that governments will eventually act and everyone else including company leaders and investors need to wake up and start acting like they know governments will eventually act (which I believe will increase the likelihood that they act sooner, which would be a ‘very good thing’).

No pun intended, but if they keep doing this, there may not be a tomorrow. No, that’s far too dire - but tomorrow may not look good from a investment returns standpoint nor a “can I enjoy my life” standpoint.

See https://www.dezeen.com/2021/06/22/carbon-trust-net-zero-carbon-neutrality-difference-interview/

Yes, yes, there are voluntary carbon credit markets and there’s a lot of heroic work going on here. But the size of the current voluntary carbon market is tiny (measured in the 100s of Mts) in comparison to the ~50Gt of global annual CO2 emissions. And if the number of corporate commitments to net zero that are already in place were to start being acted on any time soon, the demand would completely swamp the amount of supply available. More on that below.

Those that have signed up to SBTI, for instance, are in good shape. There’s more than 1000 who have signed up, like VISA or Starbucks, which is great. If you haven’t read their stuff, you should: https://sciencebasedtargets.org/. But 1000 is a tiny number in the context of the number of companies in the world. And most of the companies that have signed up are those that have important brands and care on some level what consumers think about them. There are a lot of companies, and disproportionately many amongst those who are heavy emitters, for whom consumer pressure is a lever that is unlikely to make much impact.

You could just as well call this bucket “efficiency”, but I think that avoidance is a good word that also covers “avoiding doing inefficient stuff”.

I’m not trying to pass judgment on any specific project or any companies’ portfolio. I’m not qualified to do that. Others can do that valuable work. Not all of big tech is overly reliant on these credits - MSFT does use forestry credits extensively (see: https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/coal/012921-microsoft-buys-13-million-carbon-offsets-in-2021-portfolio). However, to give them their due, they are also very focused on funding R&D in sequestration and they spend a great deal of effort trying to determine the real project outcomes vs. counterfactuals (see: https://carbonplan.org/research/forest-offsets-explainer). Stripe has focused exclusively on removing carbon from the atmosphere in a truly impressive way (see: https://stripe.com/blog/first-negative-emissions-purchases). However, these marketing claims such as “removing all historical carbon from the atmosphere” need to be held up to scrutiny and a set standard where we are actually creating a trajectory to a true net zero (from a mass balance perspective).

Or it’s equivalent in terms of regulation, I’m sure many of you are already getting tired of me saying that regulation can be the same as a price.

One late-breaking piece of news that I haven’t had a lot of time to dig into yet is this article in Nature this week. It implies that taking a ton of carbon out of the atmosphere may not do as much good (for warming) as the harm of putting one ton in. If there’s an asymmetry in removals vs. additions, that complicates things yet further and implies we might want a lower price for removals than we have for emissions, further limiting the amount of long carbon. But it’s premature to go too far down this rabbit hole based on one article.

Actually, I’ve picked a very thorny example here - if wood is used in construction vs. paper pulp vs. firewood vs. letting it rot it has very different emissions profiles. I don’t want to get into how you differentially price this and charge it back to the forest owner or end user. This minutia of carbon tax policy could (and already has) fill volumes. I think people make too big a deal about how complicated and costly taxes are; you do your best, you learn what went wrong, and you iterate. At least with carbon, you have a single clear outcome and scientific reality you’re working towards vs. say, agricultural policy.

This graph includes both avoidance and sequestration in a single graph, which is good.

For the record, I do think that the amount of nature based sequestration is vastly undercounted in potential, but that the discount factor is going to be very high because of all the risks embedded, and that until securitization, insurance, and a forward curve can be brought to bear to “normalize” these credits alongside things like CCS, DAC and mineralization it will be challenging for them to be fully taken advantage of.