Existential emitters, do-gooders, and the vast middle

Three approaches to carbon risk management in the market today

Listen to Ryanair’s FY21 earnings call (May 17, 2021) and you’ll hear a vision of the future. The carbon they emitted cost them 150 million Euros last year, and since that time the market price per ton of CO2 emitted has doubled. However, they’ve already hedged that exposure so that it doesn’t reach the ~10% of profit that it might have by one analyst’s estimate. Their planes are already more efficient than competitors - they claim that any passenger who switches to Ryanair from a legacy carrier is lowering his or her environmental footprint by 50%. So as the price of carbon rises, they believe they will steal share through price competition. They’re proud they earned a B- from the Carbon Disclosure Project, and they’re hard at work to earn an A rating. They don’t just hedge fuel costs like they used to, they are also actively hedging movement in carbon prices. And they are not resting, they are actively continuing to improve their fleet through R&D and purchases to further increase their carbon advantage vs. competitors. Does that mean that they are truly green? I don’t know - that’s an absolute question. But they are building a carbon competitive advantage and managing their climate risk as financial risk.

Every passenger switching to fly in Ryanair from a legacy airline in Europe is already reducing their environmental impact by 50%. We are determined to continue to go faster, further with ambitious environmental targets that will continue to make Ryanair Europe's greenest, cleanest airline.

Michael O’Leary, Group CEO and Executive Director, Ryanair - May 17 FY21 earnings call

Businesses and consumers buy insurance all the time for risks they can’t afford to fully bear themselves. Consumers buy home & life insurance, and airlines hedge fuel costs by purchasing futures. But we don’t insure everything we could: very few consumers buy personal property insurance, and airlines don’t typically hedge future food or paper costs - because these are risks that we can afford to take. Those smaller risks have a minimal impact on our financial well-being or a company’s bottom line. If you read The Bigger Short: Carbon last week, you know that I think that the vast majority of companies (unlike Ryanair) don’t even know what the dimensions of their carbon risk are.

There are some companies which have leaned into covering their exposure to the carbon short (I’ll call them the “existential emitters” and the “do-gooders”), and they make up a very small minority of companies1. The rest, including almost all companies, (which I’ll describe as “vast middle”) are currently treating their carbon short position as a self-insurable risk like personal property (even if they have Net Zero 2050 plans, they don’t tie to capital planning), and I’d argue that some of them are making a huge mistake - but unless they do some simple math, many won’t even know the magnitude of the financial risk they bear.

Since carbon emissions (& carbon emission futures) have been priced at zero in so many places and for so long, many CEOs and CFOs irrationally & incorrectly believe that those emissions will be priced at zero or a very low price forever. I can say with confidence that many are not yet doing the work to figure out (a) whether that’s a correct belief, or (b) how much it will cost them if they’re wrong. They don’t know if carbon is more likely to be like auto, home & life (worth insuring), or like personal property (worth living with the risk) for their company, except based on intuition. But intuition is not generally how financial leaders guide companies effectively.

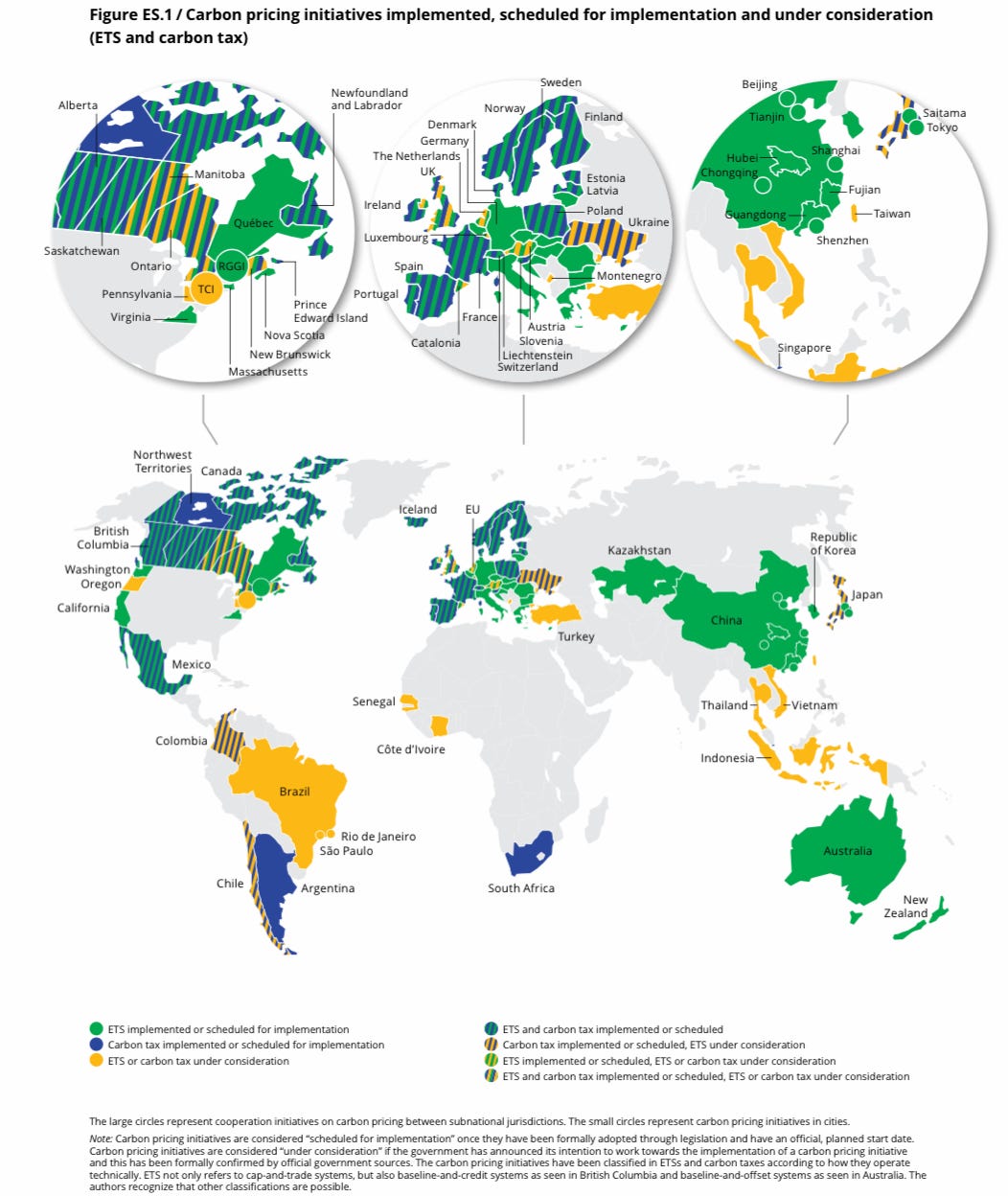

The evidence that carbon prices will not be zero forever is accumulating all over - it’s priced in some jurisdictions & sectors (EU, Canada, Nordics, …) and the list is growing fast. If there was a well-functioning futures market for carbon over a decade or longer, it’d show that the best estimate for carbon delivered in the future is certainly not zero - but there just isn’t one today.

The three types of carbon risk management

The Do-Gooders:

Alphabet / Google emitted something like 13 million tons of CO2e in 2018 - if you’re interested in what taking this challenge seriously looks like you should absolutely read Alphabet’s 2019 CDP report. For them, at $50/ton that’d be $650m every year. That’s a lot of money, but not that much to Google, who in 2018 had $137 billion of revenue and $31 billion of net income. At twice the price, however, that $1.3 billion would begin to be real money - even for Google. However, their reputation (remember “Don’t be evil”?) is likely even more important to them, as their CDP report makes very clear and so does their testimony before Congress, advertising, etc. So they’ve taken it on themselves to start reducing their footprint, and like much of big tech they have promised to be “carbon free by 2030” and they’ve already purchased offsets which are intended to take the equivalent of their historical emissions back to 1998 out of the atmosphere. No regulator or financial market is making them do that - they are doing that for a variety of reasons, including good PR (who doesn’t want carbon-free search results?) and good business (who wants to be sitting on top of that kind of commodities exposure if they don’t need to be?).

So for Google, and much of big tech (see Microsoft who was a first mover and deserves a lot of credit, Apple, Stripe, etc), it’s an easy decision - the actual cost to them of converting to zero-carbon renewables isn’t that much today as a percentage of their profit2, and the cost of going back and removing carbon equal to their historical footprint is “extra” and looks really good (and is the right thing to do; many things that look really good are also the right thing to do, and we shouldn’t give companies a hard time for doing the right thing and getting credit for it even if they’re also trying to get away with something else)3. So even though Google and their ilk emit a lot of CO2, they aren’t what I’d call existential emitters - they can afford to get the exposure to the future price of carbon off their books, and they have4. Call these the “do-gooders” (typically higher margin consumer brands with many brand risks & downsides to worry about and much brand upside to extract), and many are getting ahead of the curve through corporate commitments. Many of this group are doing this largely (not entirely) through voluntary offsets.

The existential emitters

On the other end of the spectrum there are companies in sectors like oil and gas and energy, who are what I like to call “existential emitters”. This means that emitting carbon dioxide is inherent and likely unavoidable in their core business; or to put it another way, they pull a product out of the ground that has no other way to be used other than to put CO2 into the atmosphere5. Airlines today fall into this category as well (because there’s no alternative energy source yet like electric planes or clean hydrogen that can practically pack the energy density to do what planes do without burning fossil fuels). These existential emitters have been onto this dynamic that they were speculating on the price of carbon for a long time. They have a number of different strategies. Some have begun a fairly radical shift to become renewables companies. For instance Equinor (likely the leader in this shift / dilution of carbon footprint) recently made half of its earnings from renewables - their secret is to no longer be so much of an oil & gas company; they are hedging their exposure to the future price of carbon by shifting their earnings to a lower carbon-intensity mix. Others, like BP, Shell, and many other companies are doing the same and creating large-scale carbon-trading operations, and are engaging in a number of activities to hedge their future short exposure to carbon prices by “building a long position in carbon”6 to offset their short position7.

Are these existential emitters doing what big tech has done and eliminated their short carbon position by 2030? Nope, they probably couldn’t afford to yet - in fact, as we’ll discuss later, there isn’t enough long carbon around for them to cover their current position even if they wanted to. But they are taking this really really seriously - if you read Shell’s CDP report (which you should), they are projecting $100/ton cost of CO2 emissions in all countries by 2050. They have staked a position, and they’ve started the work to begin to quantify what assets will be stranded (eg, no longer profitable / worthless), and to diversify their operations. They’re treating this as a commodity trade that they need to hedge - and while I sure don’t know, I’d be shocked if they’re not running sensitivity analysis on the timing and future price of carbon in case it’s earlier or higher. They too are beginning to unwind their exposure. Many are beginning to dilute their position through renewables and to build sources of future delivery “long carbon” as they develop & sponsor projects and/or buy equity in companies which promise to sequester carbon through nature based solutions and other novel technologies8. They may be among the “A students” within oil & gas, but they’re not alone in beginning to think this way. Lots of other folks with more knowledge than I have are analyzing the whole energy extraction sector to see who has what exposure - and the pressure from investors is already substantial. I’m not by any means saying that what they’re doing is enough. Many oil companies’ efforts & plans don’t measure up9 to Shell’s or Equinor’s, and those will be left holding more of the bag if carbon prices move fast and/or soon. But I’d make a strong wager that most if not all companies in the oil & gas sector know what their exposure is and have detailed models. If they don’t, their shareholders should be irate - and it certainly looks like as a sector they are making some progress- though they acknowledge they need the help of coordinated government regulation (in many forms, but including carbon pricing) to get there.

The vast middle

Ok, so big tech is working on this (because they can afford to), and oil & gas is working on this (because they can’t afford not to). But about other companies - what are they doing? Let’s call this set of companies (between the do-gooders and the existential emitters) the “vast middle”. I’m going to take an absolutely wild guess that these companies are responsible for 80%+ of the global emissions that can be traced back to corporates10 - whatever it is, it’s a lot.

Well, action among the vast middle is spotty at best - and that’s a nice way of saying that based on a lot of conversations, few companies are managing it the same way as either the do-gooders or the existential emitters. Carbon (when it is directly discussed & managed) typically falls under chief sustainability officers, and my perception is that in most companies in the vast middle do not have sustainability reporting to the CFO. If you’re a retailer or apparel manufacturer or food company or non-cloud operator software company or anything else, chances are you haven’t done deep detailed work on this yet. Most companies are just now getting their arms around what their emissions actually are (just over half of S&P500 companies now report Scope 1 & 2 emissions, and beyond the S&P500 it’s extremely rare); and to be fair, just a few years ago no one was asking them to do that. And regulators don’t yet have clear requirements. Most non-existential emitters only recently figured out what their emissions in 2019 were. I’d guess that they too are going to realize fairly quickly that they are playing on the carbon futures market, and some of them are going to start building up options to hedge their future exposure to the price of carbon. Some of this will be more straightforward, and we’ll see it play out in predictable ways that seem familiar at this point. Walmart already put solar panels on the roofs of warehouses and stores years ago (both because it made financial sense and because it looked good for them); this kind of action will become more mainstream. Companies already review their supply chains regularly for efficiency, they’ll incorporate fuel price volatility in their projections of where they should be sourcing from and how they transport - and perhaps they’ll hedge their risk by doing more near-shoring and on-shoring.11 As discussed above, at a given market price or regulated price of carbon, the set of things that are attractive to do will get done. That’s just what it means to maximize profitability, something which most companies are very skilled at doing. And as companies realize just how much risk they’ve onboarded, those that are more exposed will make faster moves to change their exposure - or they will be punished as their cost of capital increases.

In other words, once carbon is more obviously forecast to rise, more and more companies will have some portion of their business that is an existential emitter. Companies which learn to think & act as Ryanair is today before carbon is priced in their jurisdiction & sector have the opportunity to build a substantial competitive advantage.

Stay tuned for advice for the vast middle on what to do to get started

To be fair, the existential emitters represent an even more significant portion of emissions if you include their Scope 3 emissions - the emissions from using their products downstream.

Remember, they also do better than you or I in this, because they’re often purchasing energy wholesale and can even do large-scale renewable energy project development themselves - they buy a LOT of electricity; which means they are more protected against potential energy cost inflation.

Again, I’m not commenting here on whether the offsets they’re purchasing are actually going to do what’s marked on the tin - whether they are actually going to result in less CO2 being in the atmosphere. There is a lot of controversy about this - and they devote a fair amount of effort to making sure that the credibility of their credits is high when they purchase them. But those studies can be wrong, and a lot can happen. Even while they’ve worked on lowering risk - the real question (for another day) is who holds the climate risk (if those offsets don’t actually get the carbon out of the atmosphere) and who holds the financial risk if those offsets “go bad”. It’s complicated enough to deal with non-fulfilled forward contracts. But when those offsets are made in a world where they are voluntary credits, and there’s no single “market price” or commodity reference price, it’s super hard. The legal & risk questions will be substantial - and we’ll begin to pose them more fully in another post.

Let’s leave aside for today whether they have any residual risk for the carbon removal that they’ve done. There are a lot of things that could go wrong with these “credits” they are purchasing - the companies they’re contracting with could fail to get the carbon out of the atmosphere (delivery risk), or could take it out but it could be “impermanent” and be released back into the atmosphere (forestry projects are great, but forests can burn down), they could fail to be “additional” (we all might decide that the carbon they pulled out might have been pulled out anyways) or they might “leak” in the sense that by removing carbon here, some other carbon that goes back into the atmosphere. This is complicated and hard, and a topic all unto itself. But suffice it to say, that as with all futures contracts, there are a whole host of risks embedded that need to be hedged out themselves.

Unless you like paperweights that are filled with crude oil, which doesn’t sound like a particularly profitable line of business to me.

Please note that this is by no means a judgment - companies which emit a lot of carbon and decide to do a bunch of renewable work are doing renewable work. More renewable work should be lauded and encouraged. There is green washing (getting credit for things that don’t help), but that’s not what I’m talking about if they’re actually doing the hard work. We should care primarily about the renewable transition getting done, not who does it nor whether they get the right amount of credit for it.

In many cases, such as energy companies & transport with European exposure, they are less able to reduce exposure through purchasing international offsets because regulators / the ETS will not allow them to; however regulations are changing all the time.

One thing we all need to be aware of, however, is that some of these “long positions” in future carbon that they are building up may not pan out - they may not effectively take as much carbon out of the atmosphere as we hope or project. It does not mean that they should not try to do this work - it simply means that we need to be very mindful of who is holding the risk (execution risk, science risk, counterparty risk, permance risk, etc.) on these positions. If those positions “blow up”, it is not just a financial risk, it is a climate risk. And we need to start to pay attention to how these risks are correlated and managed.

Note that generally speaking European energy companies are ahead of their US counterparts, likely both because of the existence of carbon pricing on energy in Europe but also because of a greater cultural & political focus on sustainability. However, even the API (American Petroleum Institute - the North American lobbying group for oil & gas) has come out in favor of carbon pricing.

There’s complexity here that I’m going to shy away from completely. If an energy extractor (like Exxon) pulls oil out of the ground and refines it & ships it to you and you then put it in your car, I’m saying that the energy used to pull it up, refine it, and ship it to you falls on them - but that the cost of putting it in your car and burning it falls on you. It’s an oversimplification - you’ll bear some of the cost of the carbon in the gas and the seller of the fuel will likely bear some of it. But either way, the extractor of the fuel has to plan for (a) the direct hit to their profitability of the energy cost of getting oil out of the ground and to the end user, and (b) the impact of increased cost on end users not wanting to use as much.

There’s much to be said about the potential for climate policy to politically be linked to tariffs. Since no form of energy is “free”, increasing energy costs lead to an examination of the trade-off between distance and labor costs. If you expect certain forms of non-substitutable energy to increase (in the form of carbon pricing), you may pay some more to keep some amount of manufacturing closer to your destination market to insulate against those future price increases. This can be a powerful lever for “onshoring” or returning manufacturing to “home markets” - at least until we figure out how to move goods around at speed and without so much embedded carbon in the form of transport.