No quick fix: today’s cheap carbon offsets won’t achieve tomorrow’s climate commitments

The misleading carbon pricing baked into many corporate climate commitments will be tested soon; that’s good for corporate capital allocation decisions and the planet

Corporate willingness to spend big on a lower (or even negative) carbon footprint has increased dramatically. Large companies are making bold pledges to be on the right side of climate change. Big win for the planet?

Not according to Jonathan Foley, Executive Director of Project Drawdown, who recently said net zero commitments “have become so distorted and abused they are largely meaningless.”1 Rather than focusing on reducing their emissions, which is going to require hard, technical work to reshape supply chains, Foley says corporations are often “relying on problematic ‘carbon offsets’ to make the books look better than they are”.2

In its current state, with a surplus of low quality credits and a too-good-to-be-true low average price, the carbon market runs the risk of allowing companies to claim (whether they fully believe it or not) that they are solving their carbon footprint problem without actually making tough trade-offs or, in fact, reducing emissions. This leaves corporations — particularly the ones taking the much needed leap to make big, bold, transparent climate commitments — exposed.

They’re exposed in the carbon “short” position John Mulliken has been talking about.3 They are making plans and building budgets based on prices set by a dysfunctional market. If you believe, as we do, that the average price per tonne of carbon4 is going to increase 10x-40x before we’re at a price that reflects the kind of high quality credits that reliably remove carbon from the atmosphere, the budgets corporations have set for this challenge won’t come close to offsetting their footprints. They’ll be stuck either not delivering on the footprint reduction they promised or coughing up a lot more money to foot the impending bill.

To make this tangible, let’s look at one commitment in particular: Delta’s from February 2020. Delta is hardly the only such example, and we should applaud their transparency, which allows us to do some basic math.5

Airlines are one of the most notoriously difficult sectors to reduce emissions since there are no feasible alternatives today to jet fuel and its incredible energy density. So airlines can only do so much in the near-term without changing their core business model of flying people around. Therefore it’s reasonably safe to assume that Delta will need carbon offsets to hit their carbon neutrality target. With a commitment of $1B over 10 years, a 40 million tonne footprint (in more typical 2019, not 2020) and a conservative assumption of no growth, Delta’s stated goal of completely offsetting emissions implies a $2.50 price per credit.6

In order for Delta to keep being “carbon neutral” for the next decade and keep their budget of $1B, there are at least 3 assumptions implicit in their modeling:

A credit is a credit is a credit

The rules of carbon accounting will allow carbon offsets to be netted against their footprint

Carbon credits are plentiful and cheap

In the next decade (or even 2-3 years), all of these will prove to be bad assumptions. Though each is worth a deeper dive (I argued against #1 in my essay on the role of counterfactuals in carbon offsets), today I want to focus on #3: though there are plentiful and cheap credits today, there really shouldn’t be, and this era of cheap plentiful credits is unlikely to last.

According to the best data available, the carbon market has been “oversupplied” for the last 10+ years.7 There have been more credits created (i.e. issued) than used (i.e. retired) every year on record.8

Source: State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2020: Voluntary Carbon and the Post-Pandemic Recovery

With this excess of supply, the weighted average price per credit is low — just $3 in 2019. Let’s put that in context. The average American has an annual carbon footprint of 20 tonnes, the highest in the world. So it would cost an American $60 per year to be “carbon neutral.” If it sounds too good to be true that we could solve the climate crisis for $60 per person per year, it is.

Source: State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2020: Voluntary Carbon and the Post-Pandemic Recovery

There are two trends underway changing this too-good-to-be-true pricing: (a) an increase in demand and (b) a flight to quality.

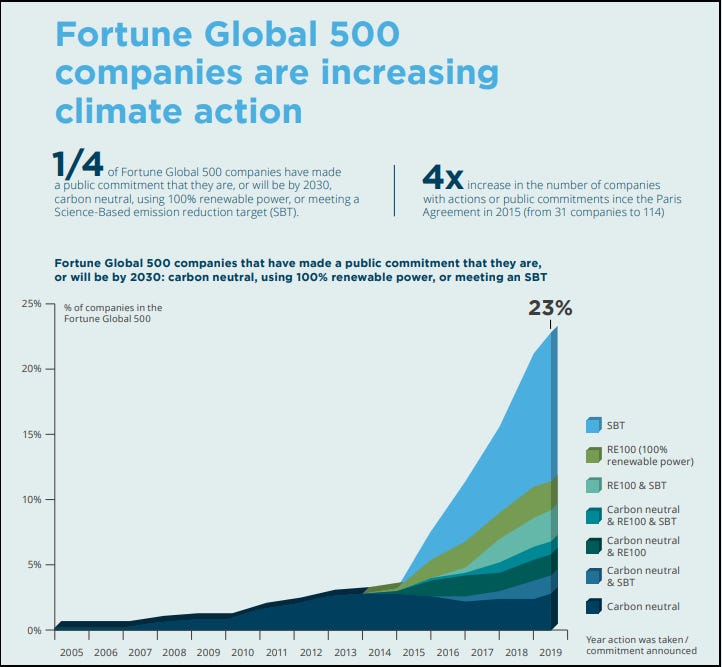

A rapidly increasing number of corporations and countries are making bold climate commitments like Delta. It’s still only 20% of the Fortune 2000, but the growth rate is heartening.9 Since many, if not all, of these corporations plan to use carbon offsets in some capacity, it is a reflection of increasing demand.

Source: Deeds Not Words: The Growth Of Climate Action

This increase in demand is leading to a flight to quality because the corporations making commitments view their brand as one of their most valuable assets. They do not appreciate being featured in articles with headlines such as, “The Real Trees Delivering Fake Corporate Climate Progress.” They want “platinum credits.”

Whole swaths of credits are falling out of favor as a result. For example, REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation) credits are increasingly viewed with skepticism, with compelling studies and articles suggesting reduced deforestation credits are not achieving the climate benefits they claim. REDD credits are the single largest source of offsets today, representing 25% of all credits ever created and 31% of available credits.10 Hesitancy to buy REDD credits would be like hesitancy to buy Saudi Arabian oil — it would create a massive supply shock.

Another swath of credits falling out of favor are abatement credits, as corporations increasingly focus on carbon removal.11 The majority of credits available today are abatement credits, but as I argued previously, it is very difficult (and expensive) to sufficiently prove the additional impact of these credits. And as John argued last week, abatement credits will have no value in a world where carbon emissions are consistently priced, which many believe is an inevitable policy response in the next decade.

This trend towards high quality credits is helping the carbon market overall. A low quality credit is easier and cheaper to create than a rigorous one, but the PR blowback from one bad project casts a shadow on the entire market, good and bad alike. The current flight to quality is a sign that the carbon market is maturing, which will bring greater credibility to the entire carbon asset class as a lever that can deliver real climate impact. There are well-organized, well-funded efforts to speed this maturation along, such as the large and influential Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets. They are developing principles to assess carbon credit quality to guide corporate purchasing behavior.

So we have two major trends: rising demand and a simultaneous rising bar for quality. Any freshman taking Econ 101 would say that’s a recipe for increasing prices, and I did a simplistic analysis in the footnote demonstrating the supply crunch if you’re interested.12 More sophisticated analyses than mine confirm that the cost of real carbon solutions is going up. Two of my favorites are from the Environmental Defense Fund and Goldman Sachs.

In 2018, the Environmental Defense Fund looked at carbon pricing scenarios given the creation and commitments of CORSIA (Carbon Offsetting and Removal Scheme for International Aviation), since that had the potential to be a large new source of demand for carbon offsets. Their analysis below plots 3 scenarios for the price per tonne of carbon offsets over time.

We should focus on the green line, since the blue and dotted lines mean we exceed a 2℃ increase in global temperatures (and we want to avoid that at all costs). Their analysis suggests carbon prices would be $34 in 2020 and $55 in 2030. And as EDF points out in their analysis, with each year of delay, the cost curve shifts higher. They wrote this report in 2018, and we have delayed 3 more years, so these cost curves have moved up.

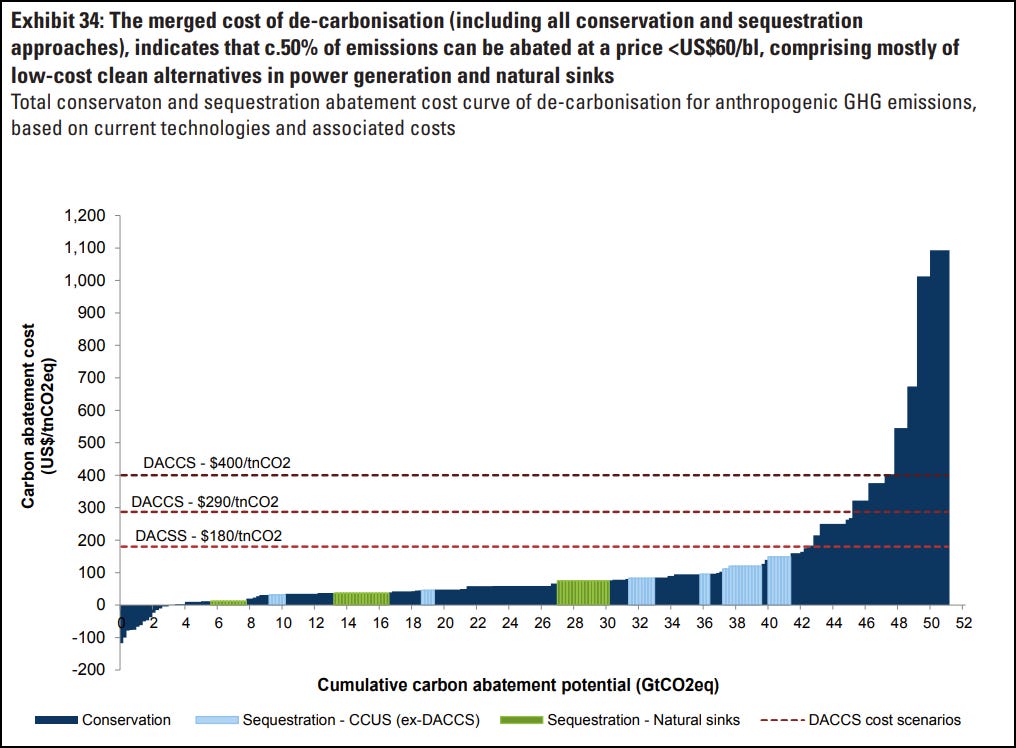

Goldman Sachs sought to answer a similar question, but they made it more accessible by plotting on a single cost curve the individual categories of climate solutions for both emissions reductions and sequestration, since the combination of those is what will generate the Net Zero future the world needs. It’s a sobering picture. We need a theoretically infinite and economically feasible direct air capture solution to come online in order to prevent a devastating cost per tonne of CO2eq, which is what the horizontal dotted red lines represent.

Source: Carbonomics The green engine of economic recovery

Circling back to our friends at Delta, the price per tonne of CO2eq only has to rise above $2.50 for Delta to exceed their $1B budget. Delta would spend their entire 2019 net profit of $1.1B on carbon offsets if the price per tonne reaches $28. $28 per tonne looks cheap in light of both EDF’s and Goldman Sachs’ studies.

When carbon prices increase, corporate climate commitments will be tested.

Earlier this month, 79 global CEOs and the World Economic Forum signed an open letter to governments around the world. They called for a short list of bold actions. Fourth on the list was, “Develop market-based meaningful and broadly accepted carbon pricing mechanisms with an escalating carbon price to enable greater competitiveness of low-carbon technologies, and control leakage through international cooperation on a global, connected carbon market.” The EDF and Goldman analyses suggest that “market-based meaningful… carbon pricing mechanisms” will bring a much higher price. The 79 CEOs confirm this in their letter by citing the The Report of the High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices, which concluded we need carbon prices of “at least US$40–80/tCO2 by 2020 and US$50–100/tCO2 by 2030”.

We need that sooner rather than later. Today, there are many who criticize corporations for hollow or deceptive commitments and question whether carbon offsets should even exist.13 And they have a point — there is a powerful moral hazard argument here. In an urgent situation, the appearance of progress is worse than no progress at all. Low price, low quality offsets are like a fig leaf hiding the fact that the emperor has no clothes.

We can’t afford that. We need every dollar we can get to be invested in climate solutions with real impact, i.e. technological innovation that makes the daily functioning of our global society and economy less CO2 intensive. And though the carbon market is dysfunctional now, the interest and requirements of corporations are forcing it to mature. As corporations make big commitments, they are demanding higher quality carbon removal, which will generate higher quality removal offsets, which will drive the price per credit up.

When rigorous carbon removal projects are priced appropriately, corporations will be less inclined to rely on offsets to achieve their commitments. The official guidance is that offsets should only be contemplated after all “technologically and economically feasible” emissions have been reduced.14 The definition of “economically feasible” changes dramatically when your alternative goes from a $3 carbon credit to a $50-$100 carbon credit. A properly functioning market for carbon offsets will be a catalyst for corporate capital allocation decisions that have a real impact on the climate because once the carbon market shifts to being supply constrained, it will take meaningful amounts of capital to achieve our commitments.

One of the key determining factors in achieving a properly functioning carbon market will be how corporations react when confronted with this market evolution. To put it in a tangible terms again:

What will Delta do when their expected price of $2.50 per credit increases — potentially by 20x or more? Will they pay the higher price to be fully carbon neutral? Will they abandon their commitment altogether? Will they spend $1B but on fewer credits? Will they shift that $1B into other activities to reduce their footprint?

What will the 79 CEO signatories of that open letter do when the carbon market matures? Will they embrace a $40-$100/tonne CO2eq price as the footnote in their letter calls for? Or will they send their government relations teams to lobby for a more earnings-friendly approach?

Today’s immature, opaque carbon market is misleading some of the corporate heavyweights who have big dollars to spend on fighting climate change. But by investing, they are changing the face of this market for the better. They just need to be ready to stick it out when the price goes up.

Ibid

First in The bigger short: Carbon and then again last week in Where’s all the long carbon?

I will use “carbon” as shorthand for CO2e or CO2eq, which stands for carbon dioxide equivalents. That is the metric that translates all greenhouse gases, like methane and nitrous oxide, into a universal standard. It’s not perfect, but it makes the conversation more fluid.

It’s important to note the unfairness in being a good corporate climate Samaritan. Only 20% of Fortune 2000 companies have made climate pledges. It’s ironic that they often suffer the slings and arrows more than the 80% with no commitments. And only “20% of existing net zero targets already meet a minimum set of robustness criteria” according to a report from the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit. So very few corporations have done what Delta has done. Delta should be applauded for their transparency. But it’s that transparency that makes them a useful test case. So with irony acknowledged and gratitude to Delta for their transparency, let’s get under the hood of their commitment.

This math is confirmed by their update from this year, where they shared that they spent $30M on 13M carbon credits, or $2.30/credit. Note that their update is for less than a full calendar year, and 2020 was no ordinary year for air travel, so their footprint is much lower than the 40M tonnes from 2019.

The best data available is from Forest Trends, which publishes their State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2020 annually. But the report issued in 2020 focuses on 2019 data. So our best data on carbon pricing is ~2 years out of date. It’s created from a survey, so it is only accurate if the sample of participants is representative of the market as a whole.

Note that this data is primarily focused on the voluntary carbon market, but it does straddle the line with compliance markets since the registries assessed do issue some credits that are also eligible in compliance markets

To “retire” a credit, the purchaser must self-report to a carbon registry that they “used” the credit. So it’s possible more credits are used than reported, but the discrepancy would have to be massive to change the answer that the market is oversupplied.

Even if the bar for quality stays the same, and hundreds of millions of REDD+ credits continue to be available for sale, the demand is outstripping supply rapidly. I did a quick arithmetic exercise for the six oil companies that have made eye-catching commitments: Shell, BP, Repsol, Eni, Total, and Equinor. Their commitments and carbon footprints are public through their disclosures. Making a few conservative assumptions, these 6 companies alone would need well over 100M tonnes in 2021 (this excludes compliance market requirements and focuses only on voluntary credits). In 2019, ~140M credits were issued in the entire voluntary carbon market.

If 25% of the world’s oil and gas companies make these commitments, we would need 400M tonnes. You can extrapolate from here to half of all oil companies, or half the Fortune 500, or half of all companies globally — the demand gets massive quickly… if corporations follow through on their commitments.

Really well-written post, I completely agree with the conclusions. It is going to be very expensive to achieve net-zero emissions for companies not making radical emission cuts, too few realize this. /Robert Höglund

Ed, this is crazy well presented, cited, and thought through. Thanks for the education.