The bigger short: Carbon

The carbon position we hold is one of the biggest financial bets we’re making, and we don’t even realize it

Few capitalists today would make lasting investments based on an assumption of zero taxes on carbon emissions…

-Economist leader, April 17 2021

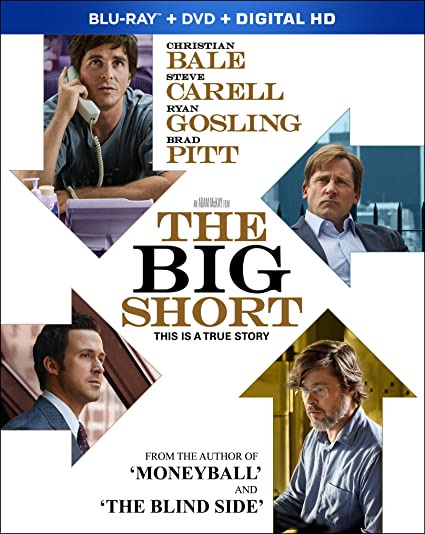

Since the movie based on Michael Lewis’ The Big Short came out, many people outside finance now know what a “short” is — a bet that something else is going to lose value. In the film, the bet was that mortgage backed securities were going to decline in value - which turned out to be a very good bet for those who made it, as the financial system froze up and the price of those mortgage bonds dropped precipitously. Those guys in the movie made a lot of money on a good bet. I’m suggesting that we (the world, investors, everyone) have made a really bad bet and we don’t even know it.

This even bigger short that we all hold is pervasive, and unfortunately it doesn’t look good. It’s an enormous financial risk effectively equal to the financial cost of climate risk. We are all, whether we realize it or not, collectively and individually engaging in commodities trading on carbon futures. Very few companies are doing the math1 on the exposure.

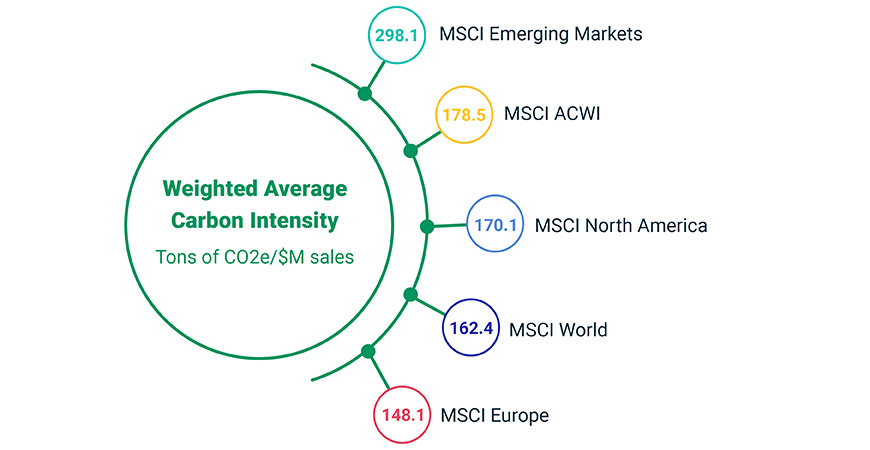

Companies around the world today embody an effective short2 on the future price of carbon, and we don’t even realize it because almost all of the carbon that they emit is priced at zero or near-zero today. The size of this short that’s embedded in companies (and households, thought that’s a topic for another day) hasn’t adequately been measured yet, and except for select assets like coal companies whose cost of capital (WACC)3 has risen dramatically in the last decade, it’s not apparent to me that it’s reflected in asset prices yet at all. This is likely an opportunity for asset managers ready to do the work to fully estimate carbon intensity and measure the embedded risk that may be mispriced, and for boards, CFOs and CEOs who are ready to think through risk management practices deployed in a context that is significantly more complex than what they’ve faced before. Why more complex? Because it’s risk management for an input cost4 that is currently priced at zero, has been priced at zero for all time up until now, has no forward price estimate or future price curve today, and the dynamics play out across many jurisdictions whose actions are linked in complex and unpredictable ways5. That all does make it complex, but not impossible to bound or estimate.

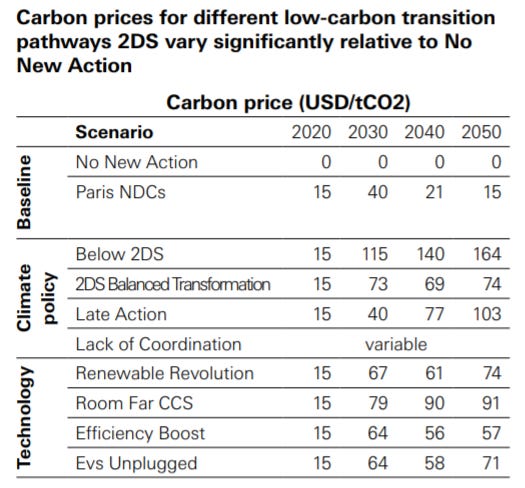

So let’s start with the basics6 - carbon pricing isn’t widespread in the US today (outside of California’s CARB & the RGGI in the northeast), but it does exist in for Europe’s ETS and many other jurisdictions, primarily for energy and transportation. Where it does exist, however, in many places the price is so low that it’s ineffective as a disincentive to emit CO2; easier to keep polluting. But as government and corporate pledges have shown, there’s a stated commitment to form “net zero” plans achieving zero carbon emissions by 2050, and some jurisdictions are putting teeth behind it. As the Financial Times reported this week, the price of CO2 emissions in Europe “soars as carbon price hits record €50”.

The price is projected to go higher, and to be imposed in more sectors. And perhaps most importantly, the imposition of a ‘border adjustment’ (which would ensure that imports to Europe would pay the same effective CO2e7 price as domestic producers) is being requested by a number of industries which feel they will be put at a competitive disadvantage. This border adjustment, assuming it happens, could well precipitate the imposition and eventual harmonization of carbon pricing in the US in order to level the playing field - and I believe that European governments and Canada are not blind to this power they wield. If the US wakes up to the ability to create a similar imposition on China (with its much greater reliance on coal and accompanying carbon intensity it’ll sure sound like a tariff, which is remarkably popular these days), we could even see movement toward global harmonization.

But as the Economist quote at the beginning of this article states quite plainly, investors who are counting on zero carbon prices continuing are making a huge bet. More and more investors and asset managers are beginning to think through the reality of the “effective short” on carbon embedded in most companies’ balance sheets that is likely mispriced today, and work is beginning to appear on creating portfolios around carbon intensity.

Calculating the value of that effective short for an individual company is not terrifically hard. I’m sure someone will come up with a more sophisticated approach, but I’ve included a quick and dirty approach in a footnote8 - it basically says “pick a future price for carbon emissions9, use that to figure out the future cost of all your future projected emissions, and take the NPV using your cost of capital.” That’s the current value of your effective short position.

For a number of businesses in certain sectors (pick software for an example, with the exception of cloud computing), this “effective short” will be de minimis relative to valuation, at least at carbon prices in the $50-$200 range. But the variance will be enormous across sectors, and enormous within sectors.

If boards, CFO’s & CEOs aren’t ready for this (up until recently, most ESG investors have relied on an alphabet soup of opaque rubrics), they should be. Work by the Carbon Tracker Initiative and the Carbon Disclosure Project are indicative of what is coming. Some investors, like Christopher Hohn, are increasingly calling for disclosure.

Larry Fink of Black Rock has made it clear that “climate risk is investment risk”. Large oil and gas extraction companies are building trading desks to assemble long positions in carbon to offset their effective short. I’d hazard a strong guess that it won’t be too long before major investors are building long positions in carbon. Unlike many of the other factors measured within the broad ESG rubric, carbon is readily measurable, auditable, and tradable.

There are many technical challenges ahead, but companies and investors should be aware of the embedded carbon short position they have, and should be managing it.

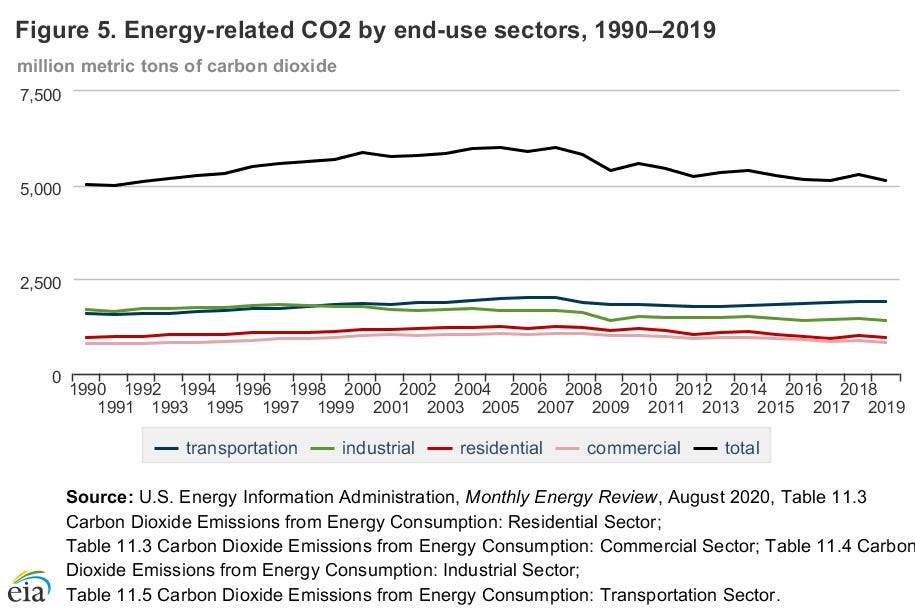

Let me frame the size of the total exposure we’re talking about in the whole world. In aggregate, if we had a $100/ton of CO2e price imposed consistently across sectors and countries (admittedly a somewhat silly back of the envelope calculation, since the social cost of carbon varies across countries and based on factors like discount rate and geographic coverage assumptions10), and we continued to emit at the same pace, the 40Gt/year would be priced at $4 trillion per year. Let that sink in for a moment. Just for reference’s sake, that’s a little more than 4% of gross global product annually.

Here’s a thought experiment - and note that if I was an academic, I probably wouldn’t walk out something which is this wonky, but I think it’s instructive. It’s super hard to get a read on what global profit margins are in a changing economy (in the middle of a pandemic no less), but for the sake of argument say they are 10%. Say that that 4% of annual product implied by a $100 price was evenly distributed across the world. If that all came due and companies had to absorb it all, it wouldn’t just be a hit to revenue, it’d all drop to the bottom line. That 4% revenue hit would be a 4 point hit to profitability, that 4 points out of 10 is 40% of total corporate profitability, and that hit would in turn wipe 40% off total valuations (until we all figure out a lower carbon intensity way to live, make things, get around, etc). Prices will almost certainly go up from the current ~$50 European cost… what about when they move to 2-3x? 40-60% off global valuations if we do nothing? Companies will act faced with this, and so 40Gt will shrink - that’s the whole point. Also, this is where the problems with these rough estimates really get bad… if the pricing were in the form of a truly revenue neutral tax / dividend, boy it would be stimulative.

The point of this is not to be chicken little and say “oh boy, valuations are going to take a huge hit!” but rather the potential for there to be winners and losers is going to be monumental with this kind of overall impact.11

Updated estimates for the social cost of carbon (SCC) are due out soon, and my guess is we’ll see those estimates rise substantially (If I were a betting person, I’d say that it’ll at least double), and prices that regulators set should eventually track to the SCC12, depending on how aggressively they choose to pursue net zero.

I’m not suggesting by any means that companies will own that whole bill. From a policy perspective, many have proposed making these carbon prices revenue neutral (so any intake that governments make is distributed and/or is used to reduce other forms of taxation) within countries, and it’s clear that developing markets will need help in making the transition to carbon-neutrality. I’d hazard a guess that the consumer will likely receive a great deal of any ‘carbon dividend’ so overall spending may be very stimulative13 with consumers buying lots of low-carbon doodads. And some carbon-related cost increases will be more easily passed on to customers than others for a while, while there are no substitutes and carbon prices haven’t ramped up that far (air travel comes to mind).

However, if & when a shift of that order of magnitude of input costs comes due, there will be winners and losers amongst those who are carbon-advantaged (lower carbon intensity) and carbon-disadvantaged, and the order of magnitude of total emissions price impact is staggering. And that’s the big carbon short. We all collectively own that short position (though asset owners really own it and are the ones who are going to be most effected when they need to unwind it). Not a good short bet, like the one in the movie, but a staggeringly bad bet.

By all accounts carbon prices are coming, but they sure don’t seem to be priced into asset values. I’m not saying that consistent global pricing will be here next year or the year after. That may be beyond the time horizon on which many — but not all — investors act. But once we get through with directly regulating the most important sources… we will have to unwind our massive and unhedged short position14.

Buckle up.

[Stay tuned for next week’s installment on “Unwinding the Big Carbon Short”]

Note that oil & gas companies got the memo a long time ago - none of the framework I’m using here will be news to them, or to the companies in big consumer tech who are already moving on this. But the vast middle of companies haven’t begun the hard work to think of this as a commodity trading & risk management issue.

I don’t want to get into the details of what an “effective short” are - I’m not a finance person enough to do it justice. Suffice it to say that owning one thing that equates to a bet on another thing going up in value is a “effective long” - so if I own stock in Gold Mining Company X that owns the rights to mine a bunch of gold that’s in the ground, and the price of gold goes up, I make money without Gold Mining Company X doing anything because I effectively own a “effective long” on a certain amount of gold through owning the company’s shares. Similarly, if I own stock in Airline Y, which has to buy jet fuel in order to run its planes (and has no substitutes), and the price of fuel goes up, and they don’t have a hedge on fuel the stock price of Airline Y goes down - in other words I own a effective short on jet fuel. Same thing goes for farmers who are going to produce a crop of wheat next year, they are “effectively long” grain, and so forth.

It’s worth noting too that this is a funny short - one in which you’re not actually betting that the price will go down (it’s zero today in most places after all) but you are betting against it going up. If you own 1% of IBM, you hold a position in a company that in theory loses a penny of value for each ton of carbon that they emit and each dollar that the price of carbon per ton goes up.

If the world starts dropping the price of carbon below zero, in effect paying you to emit more, then all bets are off and I’m buying a ticket to Mars whenever Elon Musk gets it going. Wouldn’t seem worth mentioning except I never expected to see negative interest rates in the wild until recently.

WACC = “weighted average cost of capital”. Think of this as how expensive it is for a company to get access to money to do the things it wants to do (across borrowing in the form of loans, issuing stock, issuing bonds, all the things a company does to get access to capital). If investors think a company is a good risk/bet/investment, on average its WACC will go down because more people want to give the company money, and if a company is not a good risk, it’s WACC will go up. It’s a lot more complex than that, but if you didn’t know at all what WACC was this’ll be a decent start.

So, carbon pricing is funny this way - it’s actually an “output cost” since you effectively pay for what you emit. The same thing is true for any externality that we put a price on. But for the sake of not being confusing, I’m going to call it an input cost - that’s effectively how I think that companies will manage it. Certain production processes will “use” more carbon (or in the language of MSCI - they’ll be more carbon intensive as measured by ‘tons of CO2e emitted / $1m sales’, and hence cost more - once there is a non-zero price on carbon emissions in that jurisdiction.

I’d be interested to hear from others who can name another regulation / risk management issue that has a truly multi-period global budget and collective action problem embedded in it

I’m going to skip the real climate basics that CO2 and other greenhouse gases warm the earth, and that scientists have demonstrated that truly awful things will happen if we warm the earth beyond 1.5-2 degrees Celsius vs. the pre-industrial norm, and that we are currently on a trajectory to do just that. As of a couple years ago there were about 400Gt (a Gt is a gigaton or a billion tons) of “carbon budget” remaining to be emitted before we they estimate we will hit 1.5 degrees of warming, and we were at that point emitting 50Gt per year. Despite the one-time drop due to the pandemic, it looks as though we’re projected to increase emissions in 2021 vs. 2019 - so our plans are not yet having an effect, we have not reached “peak carbon”, and we are using up our “carbon budget” (400Gt/(50Gt/year) = <10 years after 2018 unless we reduce the 50Gt/year). Greta Thunberg is far more articulate on all this than I am - like it or not, that simple math is what she is referring to when she says that we do not have a plan.

CO2e is read ‘carbon dioxide equivalent’ - in other words, emitting methane causes substantially more warming than an equivalent mass of CO2 (albeit over a shorter time period), so 1 ton of methane is counted as the equivalent of many tons of CO2, and so it has a higher CO2e.

So here’s the basic outline for a recipe for how much a company has riding on their carbon short position. We’ll come back to this when we talk about companies who may want to (or need to) put carbon on their balance sheet. I’m sure others could better formalize this approach, but I think at a first order of approximation companies should do the following:

Pick a future carbon price (or forward price curve) for each jurisdiction,

look at current emissions, assume that carbon intensity (measured as CO2e/$m sales) stays the same unless a company has committed capital projects that make you estimate differently,

and project future emissions based on carbon intensity growing in line with revenue (unless you have capital projects which specifically reduce emissions - note I’m not counting offsets here),

That gives you a future gross carbon emissions and a future price change and multiply them together to project a gross cost of emissions into the future.

Calculate the current value of that stream of projected cash flows using the company’s cost of capital, and voila presto - that’s how much economic value the company has riding on the price of carbon not rising.

Not that hard for a first cut at sizing how much a company has riding on this. Hint to asset managers and analysts - we should probably be able to do this first order analysis externally once we have current year CI data.

Even better, pick a carbon forward price curve that evolves over time. Note that a market based forward price curve doesn’t really exist yet, and we desperately need one. But there isn’t enough futures activity yet to have a publicly available index. This is very high on the list of tools needed for effectively risk-managing business against carbon. Some researchers are experimenting with very different methods to estimate and construct a forward price index from portfolios, but this is early work. We need to be able to see a transparent cost of a “10-year price of carbon” for companies to make good decisions, just as they do for debt. More on this later.

Note that this is a very rough figure drawn from a terrific paper recently published in Nature. The SCC is usually discussed as a marginal cost of an incremental ton of carbon equal to the damages / costs that are inflicted. Here the math indicates that such a balance would be achieved at an imposed carbon cost rising to above $100/ton and a world stabilizing at 1.5-2 degrees Celsius of globally averaged warming.

I think it’d be really helpful to do a few examples… let me know if you’d be interested in seeing those.

Note when I say that carbon prices “should” track to the SCC here, I’m saying “should” as an economist says it - meaning “it’d be most efficient if it did”. The SCC in the US is used today primarily for regulatory analysis and will inform EPA regulations, etc, but any real economy-wide carbon price is going to go through Congress and wouldn’t need to track with the SCC. A bill that was introduced by Senator Sheldon Whitehouse set the carbon price according to the Federal government’s assessment of SCC, but the price trajectories for all of the other bills (and even more recent Whitehouse ones) have had very different price mechanisms, with some starting low but rapidly escalating to a price well above the SCC. Thanks to Kevin Rennert of RFF for clarifying this for me - any remaining mistakes are mine.

For instance, see Canada’s system - they are giving the majority of intake back directly to individual residents. For most income levels, residents look to be on average better off (read: making money) after paying the taxes. See the table in this Wikipedia article drawn from the parliamentary budget officer.

If you were paying attention during the GameStop (GME) mayhem, you’ll have a recent visceral experience of a short squeeze. There could be a huge short squeeze on carbon. More on that later.

John, you mention in note 11 that you're happy to share examples. I have some that come to mind - what are yours?

If society is undervaluing the *cost* of carbon emissions, then isn't it going *long* rather than short?

That is, if the economy in general currently prices carbon emission at zero and expects that price to remain flat in the long term, but a tax on emissions will cause carbon emissions to have a negative value, then the value will go down contrary to expectations, which makes it a long position.

I understand that shorting carbon emissions (expecting the cost to go up, meaning the value goes down) would look like dumping unexploited fossil fuel assets, investing in green energy, and the like. Or maybe I'm confused and got it exactly backwards, that definitely happens sometimes.

Btw I found my way here via https://www.newyorker.com/news/annals-of-a-warming-planet/everyone-wants-to-sell-the-last-barrel-of-oil